Ice Palace

Learn All About the Ice Palace

Our awe-inspiring structure is meticulously crafted from thousands of ice blocks and has been a cherished centerpiece of our annual celebration. Discover its rich history, marvel at intricate designs and learn about the hard work and community spirit that brings this icy wonder to life each year.

Saranac Lake Ice Palace FAQ

The Ice Palace Story

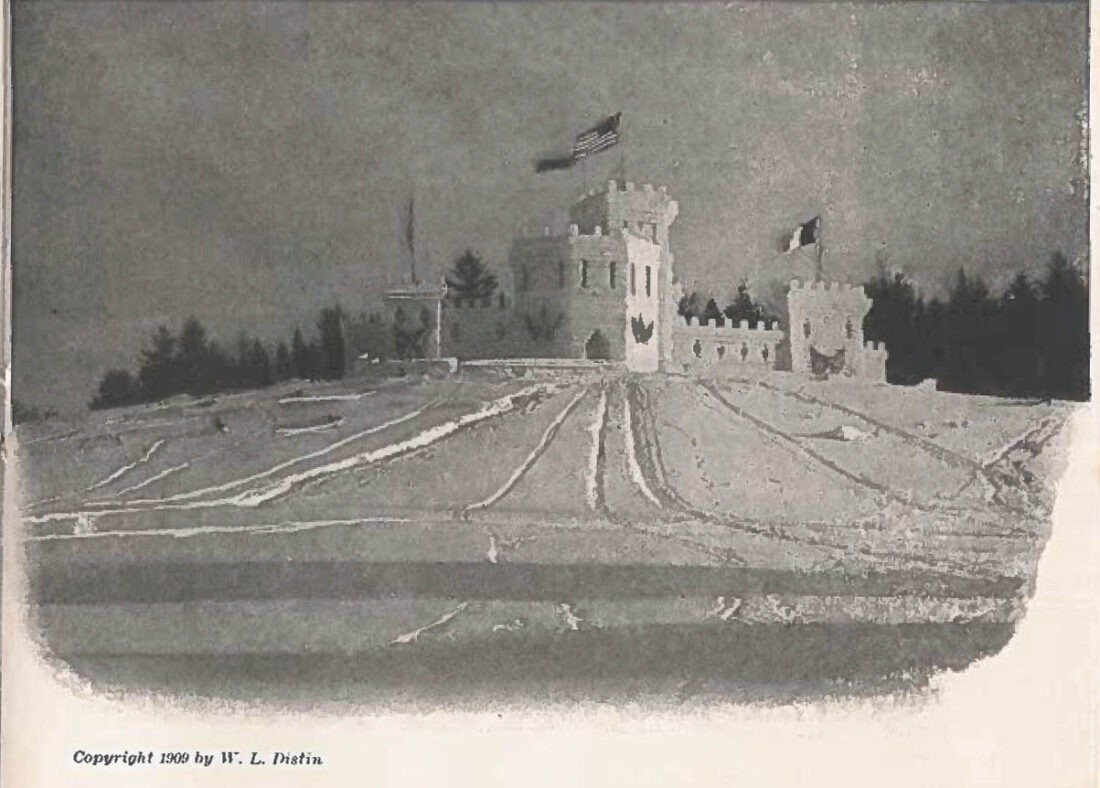

In 1898, one year after the start of Saranac Lake's first Winter Carnival, construction of an Ice Palace was added to the celebration, becoming the central focus of this event. Thereafter, magnificent Ice Palaces (or fortresses as they were also called) were built in 1899, 1900, 1901, in odd numbered years until 1911 and in random years until 1920. Palace building was suspended during World War I, the Depression and World War II but started up again in 1955.

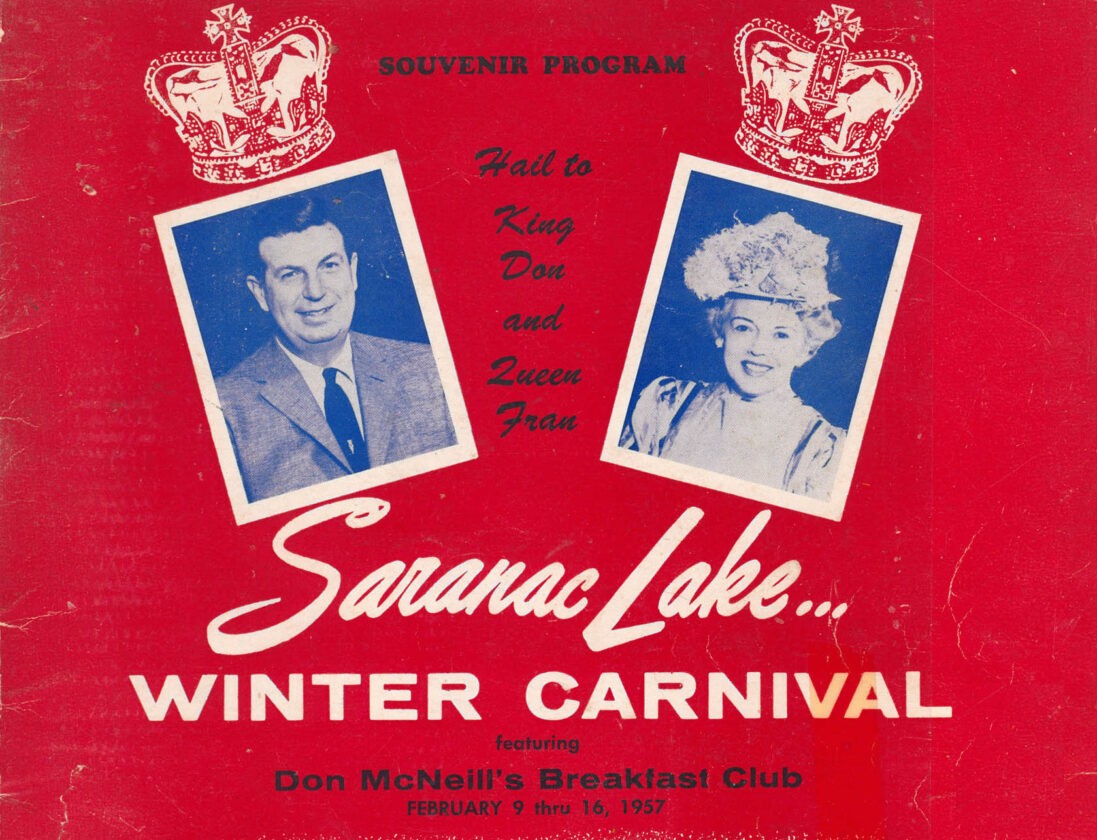

Of course, a Palace needs royal occupants, so ice thrones were placed inside these majestic residences. A king, queen and court were chosen to honor the Palace and reign over the Carnival. In the far past, kings and queens were famous invited guests such as movie stars or radio personalities but, since 1970, they have been selected to honor local residents who generously volunteer in the community.

Ice Palaces boast a noteworthy history in many respects, not the least of which is the number of well-known architects who have designed them: William L. Coulter, Max Westoff, William G. Distin, Sr. and more recently: Michael L. Bird and James W. Hotaling.

In recent years, these extraordinary structures have been designed by residents who, though not professionally trained in architecture, nevertheless, with contracting and often engineering experience, step forward and exhibit extraordinary skills as evidenced by the artistry, complexity and sturdiness of the Palaces they create.

Today a group of these volunteers meets in a local restaurant to sketch out the palace design (on a paper napkin) based on the Winter Carnival theme selected for that year. This sketch is then converted into a large blueprint which is kept on site during the building process.

Looking Back

In 1898, members of the Pontiac Club, a winter sports club founded by several men (one of whom was Dr. Edward L. Trudeau, famous pioneer of tuberculosis treatment) supported the idea of building an ice palace. As the goal of this club was to encourage good health practices and take advantage of the rugged climate, a winter carnival and the building of an ice palace clearly helped meet these objectives.

In early years, construction of the Palace was put out to bid. Ice harvesters, used to working with ice, applied for the contract. It took several weeks for the selected contractor and his men to build these mammoth centerpieces of the Carnival. According to an article by Emily Abendroth, Adirondack Daily Enterprise Weekender, 6 February 1993, they "...featured indoor rooms, staircases, towers, and battlements which soared to 60'." Those ice fortresses certainly succeeded in creating excitement and delight, not only for residents and visitors, but for the thousands of tubercular patients who were curing in Saranac Lake's bone-chilling winters.

In the 1960s, when the cost of paying for the palace construction became too much, volunteers stepped forward and took over the organizing, designing and building. That is still how it is done today.

Construction Methods

Gasoline powered saws came into use around 1919. Before that, the cutting of ice blocks was done by horses pulling an ice "plow" back and forth along a marked line to saw through the lake ice. This piece of equipment, resembling a farmer's plow had, instead of a blade, a long horizontal row of 6 to 8 large teeth which cut several inches down into the ice. Final cuts were made with manual one-handled ice saws which look very much like logging saws and are still in use today.

In 1909, 1911 – 1913 and 1920, the palaces were built atop Slater Hill (where North Country Community College now stands), most likely because of better visibility. A kind of horse-driven elevator was developed to drag the blocks up-slope to this challenging lofty site.

In the earliest years of Palace construction, horses pulled the massive blocks out of the water, assisted by men using ice tongs. A chute was slid into the water to help ease the process. Horses and later vehicles dragged the ice from the take-out point to the Palace. By the 1950's, however, a 60' chute made of telephone poles with a ramp laid across the top facilitated sliding the blocks to the palace location on the shore of Lake Flower.

Years ago, the construction of hard-packed snow ramps provided a slope to the top of the walls so blocks could be pushed up and into place. Much of the manual labor has now been taken over by the use of log loaders, cranes, excavators with claws attached and tractors and front loaders.

Today, with the use of modern equipment, lifting blocks to the top of the walls has become an easier job. Once the blocks are up there, however, the work of placing them has changed little. "High-ice" workers standing on top of narrow walls at a height of 30' or more must maintain their footing while receiving the 400 pound blocks and sliding them into position. They still use traditional antique ice shavers to do this. Shavers look a bit like slender combs with long-handles.

Other jobs which continue to require the same hard labor as over a hundred years ago include making the final cut through the ice to free each block. While gasoline powered saws are employed to make the initial deep ice cuts (See a video about the ice saw here), the final ones releasing each block are still made manually with antique ice saws.

Once free, the blocks must be pushed, again manually using antique pikes or peaveys, down a channel to the shore. Folks must still mix slush, the mortar holding the palace together, by filling endless numbers of buckets with water, pounding in snow, carrying them to the palace walls and applying the mix with rubber gloved hands that quickly become cold and sometimes wet.

Finale

Look for the abbreviation, "IPW 101" written in slush on the Palace walls. It stands for Ice Palace Workers (Union) 101. Stories vary as to its origin. One account relates that it was created as a joke in response to repeated questions from tourists who asked, "Do You Get Paid To Do This?"

Palaces have been built with anywhere from 1,000 to 4,000 primarily 2-by 4-foot long blocks and have at times measured up to 30-feet wide by 90-feet long and 60-feet high, when both weather and ice allow for it. The completed mighty fortress is always decked out with colorful flags and may contain ice furniture and sculptures along with tunnels and mazes. It draws large crowds from New York City to Montreal, Buffalo to Connecticut.

Each year, the Palace rises proudly by the shore of Lake Flower. The end of Carnival is marked by a slide show of the many varied events which take place during this great winter celebration. They are flashed onto a screen hung on the Palace Wall and are followed by fireworks exploding overhead. The glorious ice jewel of Carnival remains standing for another few weeks or until, for safety reasons, warm weather requires it be knocked down.

After carnival, in years gone by, the ice lived on in many amusing ways, one of which was to store the dismantled palace so that the following summer it could be sold to New York City customers who used it to cool their drinks. Now, it just returns to the lake until the time comes the following winter to haul it out and build it again.

This article was abstracted from "Adirondack Ice, a Cultural and Natural History" by Caperton Tissot, available at www.SnowyOwlPress.com.